Multi-Warehouse eCommerce Order Fulfillment, Pt. 1

In this post, we look at how we can use Powersets, Combinations and Permutations to calculate the number of ways we can split products in an order across multiple warehouses. We’ll make use of Python and pandas to illustrate the concepts in code.

In the beginning of every eCommerce startup, getting the orders out the door fast enough is the second best problem to have, right after getting “too many orders”.

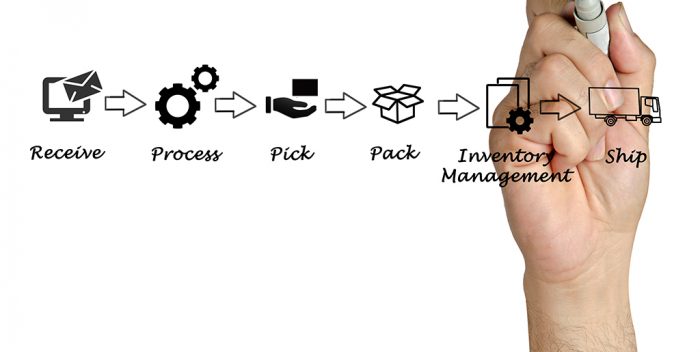

Fulfillment life looks simple at this point:

However, once the startup grows up a little and has managed the basic tackling and blocking of order fulfillment, pretty soon Operations teams start on projects to optimize warehouse processes.

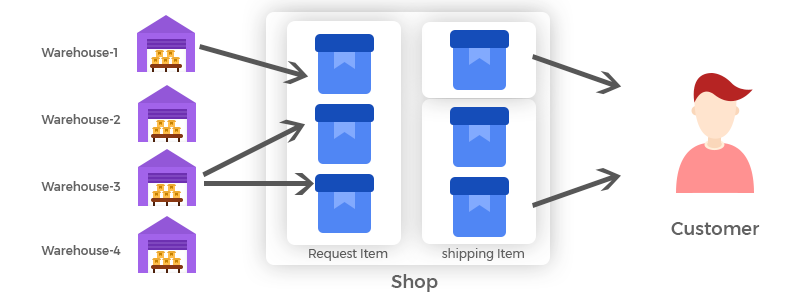

If the business is lucky enough to need more than one fulfillment center, we now have twice (or more) as many challenges. From the best location (hint: as a general rule, East of the Mississippi is where all the people live), to figuring out the optimal inventory and safety stock levels at each warehouse, there is no shortage of optimization challenges.

Split Shipments & Cross ShippingPermalink

One of those challenges that’s been occupying my mind for a while, is how to optimize (and really, minimize) split shipments.

Split shipments can happen in multi-warehouse settings when an order has to be split, i.e. fulfilled from more than one warehouse, because we didn’t have enough, or the right mix of inventory in any one location.

Cross shipping is the scenario where we have to fulfill an order from a warehouse other than the primary or preferred fulfillment location. For example, we may have a warehouse in the US in Washington State (WA) and one in Pennsylvania (PA); however, because of inventory constraints, we may have to ship an order for a customer in New York City from our WA warehouse, rather than from geographically closer PA.

Both of these are often side effects of free shipping offers.

To offer free shipping, some retailers mandate a minimum order purchase. This drives up the number of items per order, but also increases the chances that one or more items will be out of stock. [source]

As a rule, split shipments, i.e. shipping more than 1 shipment for a single order is more expensive than a single package even if we have to cross ship the order. With most carriers, such as Fedex or UPS, the overhead cost per package is typically more than the variable cost as a result of weight or shipping distance.

Which means, sending a book to a customer in NYC from our warehouse in WA, and a CD to the same customer from our warehouse in PA is more expensive in total than sending both the book and the CD from the warehouse in WA, even taking in consideration the longer distance from WA to NYC.

Therefore, one of the mantras of controlling shipping costs, and thus protecting margins in eCommerce is to minimize split shipments. (This, of course, needs to be balanced with maximizing customer satisfaction by providing fast ship times.)

Fulfillment OptimizationPermalink

Minimization of costs can be framed as an optimization problem, in which we try to find the lowest number of shipments for a set of orders given a set of inventory constraints (and perhaps other constraints, such as promised delivery dates).

Typically these sorts of route optimization problems fall under the category of set cover or network routing problems and can be tackled with modern optimization libraries in Python or Julia. In fact, with any luck, we’ll be covering the details of how to do this in (a future) part 2 of this post.

However, before we can find the optimal route, we first need to determine all the possible, or better yet, all the feasible routes.

In the classic airline scheduling problem, we typically need to first create a matrix of all the possible schedules that can cover the legs we need to fly.

So, the first step to optimizing split shipments is to determine the set of feasible routes.

Feasible RoutesPermalink

SetupPermalink

Let’s consider the following setup:

- We have a set of orders that we would like to ship today. (When we get to the optimization calculation, it’ll be an important question, whether this ship dates is allowed to slip or if there’s some flexibility.)

- Each order is made up of one or more products. If an order contains 2 or more of the same product, we’ll consider each instance of the product as a separate order line item. So instead of 2 x

P1, we think of it asP1,P1. - We have a total of 4 products we sell,

P1,P2,P3andP4 - We have 3 warehouses:

W1,W2, andW3. We chose 3 vs the more convenient 2 because if the algorithm works for n=3, it’ll likely work for n > 3. - We have limited inventory for each product at the warehouses. In fact, some products are currently only available at one of the 3 warehouses.

DataPermalink

Let’s use Python to set up some sample data for our example:

(but, first let’s import some libraries we’ll need throughout this post…)

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from itertools import *

warehouses = np.array(["W1","W2", "W3"])

n_warehouses = len(warehouses)

products = np.array(["P1","P2", "P3", "P4"])

data_inventory = [

{"warehouse": "W1", "product_id": "P1", "qty": 10.0},

{"warehouse": "W1", "product_id": "P2", "qty": 2.0},

{"warehouse": "W1", "product_id": "P3", "qty": 2.0},

{"warehouse": "W1", "product_id": "P4", "qty": 2.0},

{"warehouse": "W2", "product_id": "P1", "qty": 5.0},

{"warehouse": "W2", "product_id": "P2", "qty": 5.0},

{"warehouse": "W2", "product_id": "P3", "qty": 5.0},

{"warehouse": "W2", "product_id": "P1", "qty": 5.0},

{"warehouse": "W3", "product_id": "P2", "qty": 5.0},

{"warehouse": "W2", "product_id": "P3", "qty": 5.0},

{"warehouse": "W3", "product_id": "P4", "qty": 5.0}

]

data_orders_products = [{"order_id": 1, "product_id": "P1", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 1, "product_id": "P2", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 1, "product_id": "P3", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 2, "product_id": "P1", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 2, "product_id": "P2", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 2, "product_id": "P4", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 3, "product_id": "P1", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 3, "product_id": "P4", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 4, "product_id": "P3", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 5, "product_id": "P1", "qty": 1.0},

{"order_id": 5, "product_id": "P1", "qty": 1.0}

]

In most production scenarios, this data will likely come from a database, so let’s turn this sample data into pandas dataframes so we can work with tabular data:

df_orders = pd.DataFrame(data_orders_products)

df_orders

| order_id | product_id | qty |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | P1 | 1.0 |

| 1 | P2 | 1.0 |

| 1 | P3 | 1.0 |

| 2 | P1 | 1.0 |

| 2 | P2 | 1.0 |

| 2 | P4 | 1.0 |

| 3 | P1 | 1.0 |

| 3 | P4 | 1.0 |

| 4 | P3 | 1.0 |

| 5 | P1 | 1.0 |

| 5 | P1 | 1.0 |

df_inventory = pd.DataFrame(data_inventory, columns=["warehouse", "product_id", "qty"])

df_inventory

| warehouse | product_id | qty |

|---|---|---|

| W1 | P1 | 10.0 |

| W1 | P2 | 2.0 |

| W1 | P3 | 2.0 |

| W1 | P4 | 2.0 |

| W2 | P1 | 5.0 |

| W2 | P2 | 5.0 |

| W2 | P3 | 5.0 |

| W2 | P1 | 5.0 |

| W3 | P2 | 5.0 |

| W2 | P3 | 5.0 |

| W3 | P4 | 5.0 |

Now, to make this work a little better for the combinatorics we need to do later, we need to convert all the product rows for each order into a new column on the order, like so:

# bring order products as list to rows:

df_orders_products = pd.DataFrame(df_orders.groupby(["order_id"])["product_id"].apply(lambda x: x.tolist()),

).rename(columns={"product_id": "product_list"})

df_orders_products

| order_id | product_list |

|---|---|

| 1 | [P1, P2, P3] |

| 2 | [P1, P2, P4] |

| 3 | [P1, P4] |

| 4 | [P3] |

| 5 | [P1, P1] |

If you had sourced this data from your production database or a data warehouse, you’ll probably want to do some of this pre-work in the database. For example, splitting multi-unit orders into separate rows or moving rows to columns, for example via a listagg function, is often more scalable in SQL.

Product CombinationsPermalink

Before we can figure out the ways to split an order, we first need to calculate the possible ways we can combine the products in each order.

Let’s say we have 2 products, P1 and P2, in an order. Intuitively, we could fulfill this order by shipping P1 by itself and P2 by itself, or P1 & P2 together.

So, we’d like to make subsets of these sets of length 1 up to the length = length of the set. Turns out, this is known as a Powerset, and one way to calculate this is:

def powerset(iterable, min_elements=0):

s = list(iterable)

return chain.from_iterable(combinations(s, r) for r in range(1, len(s)+1))

So, given an iterable (i.e. an array or list), we’ll return a list of the combinations of the elements.

For example, given a list like [1,2,3], the corresponding powerset would be:

() (1,) (2,) (3,) (1,2) (1,3) (2,3) (1,2,3)

Powesets, by definition, include instances of 0 elements (the empty set) and the min_elements argument here supports this; however, for our purposes, we only care about sets with at least 1 element, so we’ll parameterize this function accordingly.

We will make use of pandas’ ability to broadcast functions to all rows, by using apply, instead of writing explicit for loops. That way, we’ll set ourselves up to scale this to possibly millions of orders from the start.

Since the powerset function returns tuples, we’ll use a helper function to turn these into lists:

tuples_to_list = lambda iterable: [list(c) for c in iterable]

And now we’re ready to apply this to each of our lists of products per order:

df_orders_products["product_combos"] = df_orders_products.apply(

lambda x: tuples_to_list(powerset(x["product_list"], 1)),

axis=1)

(Note that axis=1 tells pandas to apply the function to each row.)

The results are sets of sets of products for each order, containing a minimum of 1 element. Note, for example, that order #4 consists of only 1 product, so the resulting powerset contains a single set of P3.

Another interesting example is order #5 containing 2 units of P1; the corresponding powerset is [[P1], [P1], [P1, P1]]. That is, if a customer orders 2 units of P1, we could either ship both from the same warehouse, or ship each unit from a different warehouse.

df_orders_products

| order_id | product_list | product_combos |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | [P1, P2, P3] | [[P1], [P2], [P3], [P1, P2], [P1, P3], [P2, P3… |

| 2 | [P1, P2, P4] | [[P1], [P2], [P4], [P1, P2], [P1, P4], [P2, P4… |

| 3 | [P1, P4] | [[P1], [P4], [P1, P4]] |

| 4 | [P3] | [[P3]] |

| 5 | [P1, P1] | [[P1], [P1], [P1, P1]] |

Valid Order SplitsPermalink

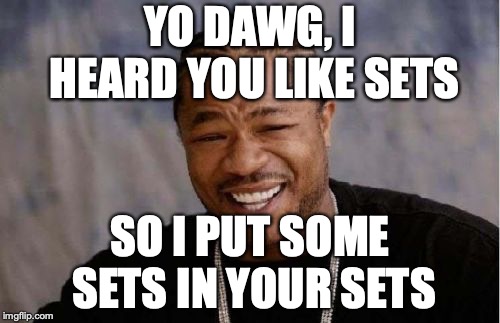

Now, for our next trick, we’re going to take these sets of ordered products and create powersets of those. I know, what you’re going to say:

The intuition is here is that so far we’ve figured out how many ways we can combine the individual products in our orders, but now we need to know how ways we can ship these groupings, given that we have n number of warehouses.

We’re going to call these splits to indicate that they represent the ways we can split an order among our warehouses. We’re not yet concerned with which warehouse they could be assigned to, just that given some n number of warehouses, and k number of product groupings we can split an order m ways.

We’ll again introduce a function to do that.

First, the function calculates all splits, which is a powerset of the previously computed product_combos, with a minimum number of elements equal to our number of warehouses.

Then, we filter these splits to make sure that:

- taken together, they cover the entire order. So, if we have an order consisting of

P1,P2andP3, the combination[P1, P2]and the the combination[P2, P3]together exceed the products ordered, so we don’t consider it to be valid. - they don’t contain a number of members exceeding our number of warehouses.

def get_valid_splits(products, product_combos):

splits = tuples_to_list(powerset(product_combos, n_warehouses))

# we only accept splits that, together, cover the whole order

valid_splits = [s for s in splits if sorted(flatten(s)) == sorted(products)]

# we only accept as many splits as we have warehouses

valid_max_wh_splits = [s for s in valid_splits if len(s) <= n_warehouses]

return valid_max_wh_splits

We, again, apply this function to our dataframe to compute the “valid_splits” column:

df_orders_products["valid_splits"] = df_orders_products.apply(

lambda x: get_valid_splits(x["product_list"], x["product_combos"]),

axis=1)

Let’s take a look what that does for order #1:

-

The customer ordered products

[P1, P2, P3] -

The possible combinations of products (

len > 1) are:

[['P1'],

['P2'],

['P3'],

['P1', 'P2'],

['P1', 'P3'],

['P2', 'P3'],

['P1', 'P2', 'P3']]

- The valid order splits resulting from those combos, given that we have

3warehouses are:

[[['P1', 'P2', 'P3']],

[['P1'], ['P2', 'P3']],

[['P2'], ['P1', 'P3']],

[['P3'], ['P1', 'P2']],

[['P1'], ['P2'], ['P3']]]

So, we get all the possible ways we could split a 3 product order across 3 warehouses: from shipping all 3 products from the same warehouse, to shipping various 2 product combos from 2 out of the 3 warehouses, to shipping each of the 3 products from separate warehouses.

Feasible Order-to-Warehouse AssignmentsPermalink

Our last job for this round, is to create feasible routes of these splits from one of our actual warehouses.

So far, we know that we could fulfill order #1 from 2 warehouses like so: [[P3], [P1, P2]], we haven’t yet assigned either split to a warehouse.

Remember, in a future post we’re looking to determine the optimal order-to-warehouse assignment, in which we might consider shipping distance and costs; so we’ll need to know which split can be fulfilled from an actual warehouse.

For now, the only constraint we’ll solve for here is looking at whether a warehouse currently carries the product. We’re not optimizing over available quantities and order demand, we simply want to make sure the warehouse carries this product at all.

In a way, we’ll want to restrict the routes we’ll calculate by filtering it through the inventory data we’ve set up. This is somewhat analogous to an inner join in database parlance.

However, since our products here are nested inside our valid_splits tuples, we can’t make use of pandas’ join syntax.

Instead we’ll have to resort to a base Python approach, filtering arrays.

So, first we’ll convert the inventory data to a simple n x 3 array:

inventory = df_inventory.values

[['W1', 'P1', 10.0],

['W1', 'P2', 2.0],

['W1', 'P3', 2.0],

['W1', 'P4', 2.0],

['W2', 'P1', 5.0],

['W2', 'P2', 5.0],

['W2', 'P3', 5.0],

['W3', 'P1', 5.0],

['W3', 'P2', 5.0],

['W3', 'P3', 5.0],

['W3', 'P4', 5.0]]

Then we’ll set up a helper function that returns the inventory quantity for a given product and warehouse:

def get_inventory(product, warehouse):

return [inv[2] for inv in inventory if product == inv[1] and warehouse==inv[0]]

For the next step, we’ll again dig into our combinatorics bag and pull out one last helper, permutations.

The code here, while Pythonic in its list comprehensions, is maybe a little opaque (in fact, I had help from the magic of Stack Overflow on this one), so let’s take a look at it, and then break it down a bit:

def assign_to_warehouses(splits, warehouses, n_splits):

routes = zip(repeat(splits), permutations(warehouses, n_splits))

assignments = []

for split, warehouse in routes:

possible_assignment_ = tuple(zip(split, warehouse))

has_inventory = np.alltrue([np.sum(get_inventory(p, wh)) > 0 for prd, wh in possible_assignment_ for p in prd])

if has_inventory:

assignments.append(possible_assignment_)

return assignments

If we consider our example split, [[P3], [P1, P2]], what we’re trying to get to is something like this:

[P3] Warehouse 1, [P1, P2] Warehouse 2

[P3] Warehouse 2, [P1, P2] Warehouse 1

[P3] Warehouse 1, [P1, P2] Warehouse 3

[P3] Warehouse 3, [P1, P2] Warehouse 1

[P3] Warehouse 2, [P1, P2] Warehouse 3

[P3] Warehouse 3, [P1, P2] Warehouse 2

Hopefully this example shows why permutations come in handy here: sending P3 from Warehouse 1 and [P1, P2] from Warehouse 2 is operationally very different from sending P3 from Warehouse 2 and [P1, P2] from Warehouse 1.

So, the code above takes the permutation of warehouses and the number of splits we’re trying to allocate and aligns with the repeated splits to get something of a cross-product of splits to permutated warehouses.

Moreover, we want to check that the given warehouse actually carries the given product. In a SQL setting, we’d accomplish this via a left outer join. However, since we’re dealing with Python lists and arrays, we have to create our own mini-implementation of a join in this snippet from the assign_to_warehouses function.

In here, we use the get_inventory function shown earlier to check each product/warehouse combination. Only if all products are available in all all warehouses, do we consider this a valid route for the split.

...

has_inventory = np.alltrue([np.sum(get_inventory(p, wh)) > 0 for prd, wh in possible_assignment_ for p in prd])

...

As before, we apply this function to our dataframe. Remembering that the valid_splits contains not just one split (as our example above), but all valid split for an order, we apply the assignment function in a quick list comprehension for loop.

df_orders_products["routes"] = df_orders_products.apply(lambda x:

[assign_to_warehouses(split, warehouses, len(split))

for split in x["valid_splits"]],

axis=1)

The result may be a little hard to view in the dataframe in total, so let’s look at one order, Order #3, to see what we’ve computed.

It’s a simple 2 product order, made up [P1, P4], which has valid splits of:

- shipping [P1, P4] together, or

- shipping [P1] and [P4] separately

example_order_routes = df_orders_products[df_orders_products.index == 3]["routes"].values[0]

We’ll write a basic print loop through the nested lists to look at the feasible routes for these splits:

for i, order_splits in enumerate(example_order_routes):

print(f"Split {i+1}")

for o, order_split in enumerate(order_splits):

print(f"\tRoute {o+1}")

for s, split in enumerate(order_split):

print(f"\t\t{split[0]} ship from {split[1]}")

print("\t---------------------------------")

What we see is that we have 2 valid splits (2 x 1 products, and 1 x 2 products) that result in 9 routes across 3 warehouses:

Split 1

Route 1

['P1', 'P4'] ship from W1

---------------------------------

Route 2

['P1', 'P4'] ship from W2

---------------------------------

Route 3

['P1', 'P4'] ship from W3

---------------------------------

Split 2

Route 1

['P1'] ship from W1

['P4'] ship from W2

---------------------------------

Route 2

['P1'] ship from W1

['P4'] ship from W3

---------------------------------

Route 3

['P1'] ship from W2

['P4'] ship from W1

---------------------------------

Route 4

['P1'] ship from W2

['P4'] ship from W3

---------------------------------

Route 5

['P1'] ship from W3

['P4'] ship from W1

---------------------------------

Route 6

['P1'] ship from W3

['P4'] ship from W2

---------------------------------

The next, computationally and conceptually harder step will be to determine the optimal routes that minimize shipping costs that cover all our order demand in the fact of inventory constraints.

Hope you enjoyed our brief excursion into combinatorics!

Comments