Solving a Production Problem using Linear Programming in Julia - 2 Ways

This post has been upgraded to use Julia 1.1 and JuMP 0.19.

I’ve been trying to teach myself Julia and Linear Programming/Optimization via Julia, so I’ve been reading a number of books on both topics. Among them is the excellent Introduction to Operations Research by Hillier & Lieberman. It presents a range of Operations Research issues and is implementation agnostic, but has a number of examples drawn from business that make for good projects to implement on your own.

Surprisingly, there aren’t a lot of practical examples out there implementing business problems using JuMP or other packages (e.g. PuLP in Python). Given the immense business value of Linear Programming, I can only ascribe this to the current fascination with ML and Deep Learning taking up otherwise valuable blog real estate.

So, to add to the small canon of LP example posts, I’ve taken an example from pg. 617, “Making Choices When the Decision Variables Are Continuous” about a production challenge faced by the Good Products Company that I attempted to implement in Julia, using the JuMP package.

Here’s the setup (from pg. 617):

The Research and Development Division of the GOOD PRODUCTS COMPANY has developed three possible new products. However, to avoid undue diversification of the company’s product line, management has imposed the following restriction.

Restriction 1: From the three possible new products, at most two should be chosen to be produced.

Each of these products can be produced in either of two plants. For administrative reasons, management has imposed a second restriction in this regard.

Restriction 2: Just one of the two plants should be chosen to be the sole producer of the new products.

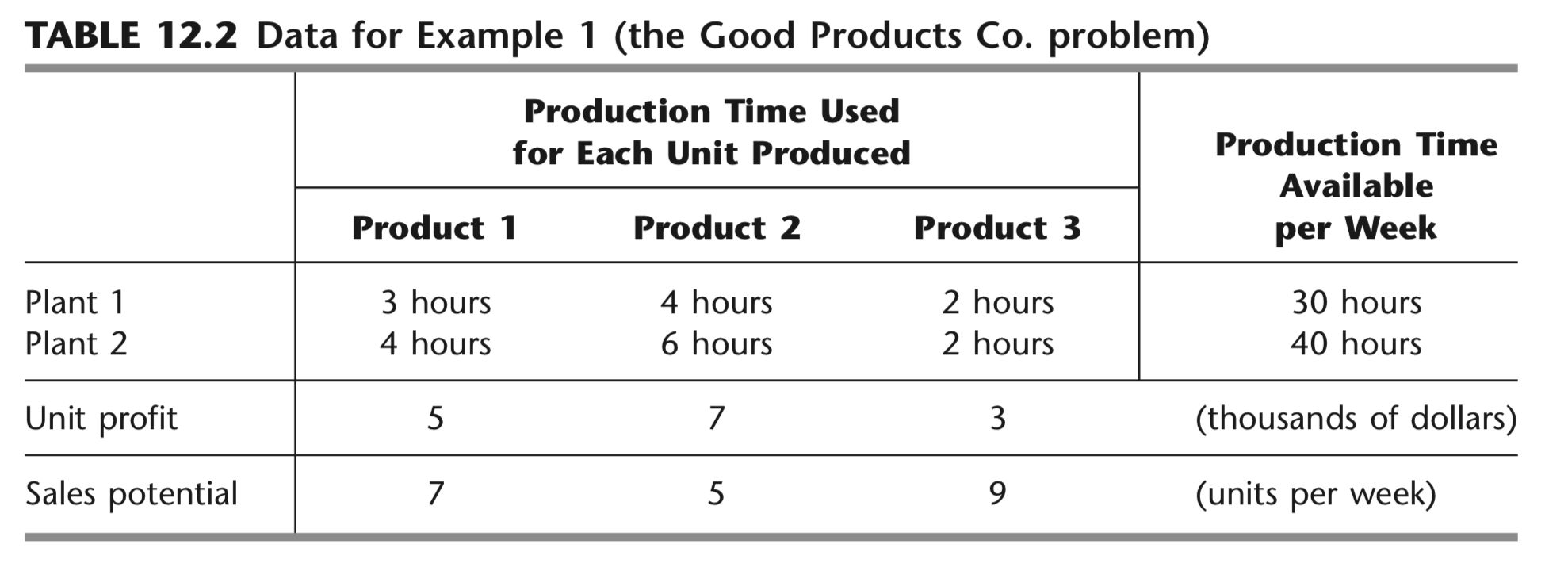

The production cost per unit of each product would be essentially the same in the two plants. However, because of differences in their production facilities, the number of hours of production time needed per unit of each product might differ between the two plants. These data are given in Table 12.2, along with other relevant information, including marketing estimates of the number of units of each product that could be sold per week if it is produced. The objective is to choose the products, the plant, and the production rates of the chosen products so as to maximize total profit.

We also get this data table:

So, we learn from the problem setup that we are to maximize profits with respect to a number of production constraints, some of which are quite tricky. Also, notice this is a Mixed Integer Program (MIP), since our production rates are decimals, while some of our constraints are going to be integers.

For instance, restricting production to just one plant is going to require us to implement either/or logic, which goes slightly beyond plain vanilla toy examples.

To make things more interesting, and to highlight a couple of cool things about JuMP, we’ll implement this problem in two approaches:

-

Using standard notation and explicit variables - we’ll call this the Direct method, since it most resembles what you see on the page. (One one of the advantages of JuMP is that you can write the Julia code almost exactly as written in the mathematical notation!)

-

Using Matrix Notation - this isn’t always how these kinds of problems are presented but it’s good to know how to do this, since it makes for a much more scalable and compact implementation.

Let’s dive in!

Direct MethodPermalink

From the book we learn that we want to end up with this model formulation:

Where through represent the production quantities of products 1 through 3, and through are decision variables representing whether or not we should even produce that product. Variable is another binary decision variable indicating whether these products will be produced at Plant 1 or 2.

Also, notice that we’re using the concept of “Big M” here as a way to implement the Either/Or constraint mentioned earlier. A value of M chosen to be “large enough” will ensure that only constraints 1 or 2 are true depending on the value of .

Since I probably butchered that explanation of “Big M”, I recommend you consult Hillier & Lieberman for a better review of the concept, but definitely file that under “stupid optimization math tricks”.

From the book (Chapter 12.3, pg. 587):

note that makes , which reduces the new constraint to the original constraint . On the other hand, makes so large that (again assuming a bounded feasible region) the new constraint is automatically satisfied by any solution that satisfies the other new constraints, which has the effect of eliminating the original constraint .

We choose to be 10,000, although according to the book, 9-10 seems to be enough in this case. How “big” needs to get depends on the context, and you don’t want to choose a value too big to avoid numerical issues.

M = 1e4

Now the Model:Permalink

Before we start, let’s make sure we have all the required packages installed, via:

using Pkg

Pkg.add("JuMP")

Pkg.add("Cbc")

(Or, use the new package manager introduced in Julia 1.0.)

Now, we set up the model using the open source Cbc solver, although for this problem any linear solver should work.

m = Model(with_optimizer(Cbc.Optimizer))

Then we set up the x and y constraints, along with our profit objective that we’d like to maximize:

# Product quantity variables

@variable(m, x[1:3] >= 0)

# Product & warehouse decision variables

@variable(m, y[1:4] >= 0, Bin)

# Objective: maximize profit

@objective(m, Max, 5x[1] + 7x[2] + 3x[3])

Now we’re going to add constraints that make sure that a) we’re not exceeding our plants’ production capacities, and b) we’re only producing at 1 plant, made possible by the “Big M” trick.

In the case of , the first constraint reduces back to the original constraint, which means that Plant 1’s production constraint is in effect. At the same time, the right side of Plant 2’s production constraint gets very large ( in our case), which has the effect of eliminating the original constraint.

The inverse is tue for and we effectively get the required either/or constraint. As I said, “stupid optimization math trick”.

# Production Restriction Plant 1

@constraint(m, 3x[1] + 4x[2] + 2x[3] <= 30 + M*y[4])

# Production Restriction Plant 2

@constraint(m, 4x[1] + 6x[2] + 2x[3] <= 40 + M*(1-y[4]))

Then we add the maximum sales capacity for each product we’re given:

# Sales Capacity:

@constraint(m, x[1] <= 7)

@constraint(m, x[2] <= 5)

@constraint(m, x[3] <= 9)

And we make sure we only make 2 of the 3 products, as required:

# Only make 2 products

@constraint(m, y[1]+ y[2] + y[3] <= 2)

Lastly, we make sure we calculate production rates for products we actually intend to make, again employing “Big M”. So, if is 0, i.e. we don’t make the product, we shouldn’t calculate a value for which is enforced by . However, for , the constraint becomes and is always satisfied in our example.

for i=1:3

@constraint(m, x[i] <= M*y[i])

end

Print the entire model and make sure it matches your requirements before solving:

@show m

Now we solve and retrieve our variable values:

optimize!(m)

println("Profit: ", objective_value(m))

println("Warehouse: ", value(y[4]) == 1 ? "Plant 2" : "Plant 1")

for i=1:3

println("y $i: ", value(y[i]))

end

for i=1:3

println("x $i qty: ", value(x[i]))

end

Profit: 54.50000000000114

Warehouse: Plant 2

y 1: 1.0

y 2: 0.0

y 3: 1.0

x 1 qty: 5.500000000000061

x 2 qty: 0.0

x 3 qty: 9.0

Thus, we make 5.5 units of Product 1 and 9 units of product 3 at Plant 2 for a total profit of $54,500, which matches the solution provided in the book. Nicely done!

While this was fun, it’s easy to see how explicitly coding each variable gets tedious quickly and certainly won’t scale well. So, let’s see how we can improve this implementation using matrices!

Matrix MethodPermalink

Using the Matrix-based approach, we use Linear Algebra to multiply a matrix of (decision) variables by a matrix of cost or profit variables. Since we can construct matrices easily programmatically or from data stored in databases or data files, this makes dealing with a large number of variables much more feasible.

First, we translate the problem set up from the book in Table 12.2 into a set of matrices:

n_products = 3

profit = [5 7 3]

production_time = [[3 4 2], [4 6 2]]

available_production_time = [30, 40]

sales_potential = [7, 5, 9]

Notice how we simply translate the rows and columns from the table into our matrix rows and columns. (Actually, I’m lying, it took me about half an hour or more to get this right, but it is pretty obvious in hindsight.)

ModelPermalink

Again, we set up our base model and variables. Here I’m using a slightly different approach, using a variable to denote the upper bound for our product variables, and I’ve implemented the variable as a standalone variable instead of .

“Big M” remains at 10,000.

M = 1e4

m2 = Model(with_optimizer(Cbc.Optimizer))

@variable(m2, x[1:n_products] >= 0)

@variable(m2, y[1:n_products] >= 0, Bin)

@variable(m2, plant >= 0, Bin)

Then to add our objective, to maximize profit, we multiply the profit-per-product vector by the vector of x variables and sum across.

# Objective: maximize profit

@objective(m2, Max, sum(profit * x))

In this next section, we loop through all available plants and evaluate which plant’s constraint we’re adding via Julia’s ternary operator. We could easily extend this to any number of plants and adjust our logic accordingly.

# Constraint: don't exceeed production time

for c = 1:size(production_time, 1)

v = c==2 ? 1-plant : plant

@constraint(m2, production_time[c,1] * x .<= (available_production_time[c] + M*v))

end

Lastly, we add the remaining constraints using vecorized dot operators.

@constraint(m2, x .<= sales_potential)

@constraint(m2, x .<= M * y)

(This last bit uses the Julia broadcast inequality operator .<= so we don’t have to write a loop to implement this constraint, which makes sure we don’t calculate production rates for any products we’re not actually planning on making.)

Lastly, we make sure that we don’t make more than 2 products, as required:

@constraint(m2, sum(y) <= 2)

And, behold, here’s the full model, which matches the model we implemented using the direct method:

Again, we solve and retrieve our variable values, which match our earlier solution.

optimize!(m2)

println("Profit: ", objective_value(m2))

println("Warehouse: ", value(plant) == 1 ? "Plant 2" : "Plant 1")

for i=1:3

println("y $i: ", value(y[i]))

end

for i=1:3

println("x $i qty: ", value(x[i]))

end

Profit: 54.50000000000114

Warehouse: Plant 2

y 1: 1.0

y 2: 0.0

y 3: 1.0

x 1 qty: 5.500000000000061

x 2 qty: 0.0

x 3 qty: 9.0

ConclusionPermalink

Hopefully this all made sense and highlighted a few things:

- JuMP is an amazing package to implement LP problems since it allows us to write Julia code matching the mathematical notation almost line by line

- The Matrix Method, while maybe a little harder to intuitively grasp initially provides a robust and scalable approach to solving large liner models

Let me know if you have any feedback on this. I’m still in the early stages of learning about Linear Programming and Julia, so if you know of a better way to do this, I’d love to hear it!

Comments