SQL Window Functions to Pass a Data Analytics Interview (Opinionated SQL Series Part 2/N)

I’ve phone screened and interviewed a lot of candidates that have gone through data analytics or data science coursework, and rate themselves quite highly on their SQL skills, but then manage to not be able to construct a simple Top N query. This is typically an automatic pass.

SQL is, and has been, the lingua franca of data. If you’re in Finance, you know Excel like the back of your hand, or better. If you’re “in data”, you should know SQL the same way.

Oh, you say SQL isn’t as important anymore in a world of machine learning and noodle neural networks? Apparently you haven’t had an interview with companies such as Netflix or Facebook or Amazon in a while then.

Let’s look at this post as a kind of cheat sheet to at least get past that stage of the data analytics interview. Or, if you’re a hiring manager, feel free to use this is a tech screen checklist.

SetupPermalink

All of these examples are drawn from real examples I’ve used in projects. Many times doing this in your database is the easiest, fastest and best way to do this in production. Sorry, pandas.

(If you’re looking for more SQL for data warehouse queries or a refresher, I have something here for you.)

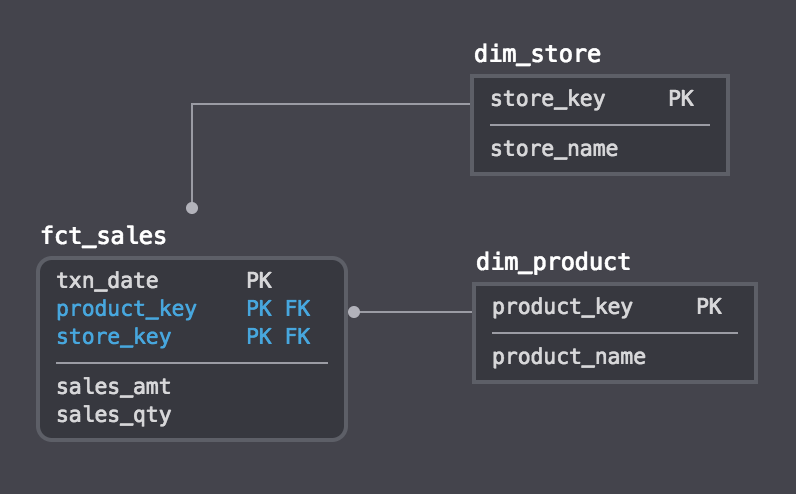

For all examples, let’s assume we’re working with a Kimball style dimensional data warehouse, where we have some sales data in a table called fct_sales, product data in dim_product and store data in dim_store.

fct_sales sample data:

| txn_date | product_key | store_key | sales_amt | sales_qty |

|------------|-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

| 2018-01-01 | 12 | 6 | 125 | 5 |

| 2018-01-01 | 23 | 5 | 154 | 4 |

| 2018-01-01 | 19 | 1 | 178 | 5 |

...

| 2018-05-31 | 8 | 2 | 186 | 6 |

| 2018-05-31 | 18 | 4 | 165 | 8 |

| 2018-05-31 | 12 | 4 | 87 | 12 |

dim_product sample data:

| product_key | product_name |

|-------------|--------------|

| 8 | Product 8 |

| 9 | Product 9 |

| 10 | Product 10 |

...

| 22 | Product 22 |

| 23 | Product 23 |

dim_store sample data:

| store_key | store_name |

|-----------|------------|

| 1 | Store 1 |

| 2 | Store 2 |

| 3 | Store 3 |

| 4 | Store 4 |

| 5 | Store 5 |

| 6 | Store 6 |

Top N by SomethingPermalink

As handy as it is to do Top N in the BI layer, it’s not always an option on every platform (looking at you Mode), so it’s good to know how to do this in pure SQL.

Let’s first look for the Top 20 Products in terms of Sales:Permalink

-- first we need to aggregate our large fact table to the grain of interest,

-- in this case sales qty by product, over some time frame

-- (because we always want a date in DW World)

with sales as

(

select

p.product_name,

sum(f.sales_qty) as sales_qty

from

fct_sales f

join

dim_product p on f.product_key = p.product_key

where

f.txn_date between

'some_date' and

'some_other_date'

group

1

),

-- then we rank the products using a dense_rank() to avoid ties

-- (experiment with different ranking functions here, use your own business rules)

ranked as

(

select

product_name,

sales_qty,

dense_rank() over(order by sales_qty desc) as sales_rank

from

sales

)

-- then pick out the top N products (you could even do this in the BI layer)

select

sales_rank,

product_name,

sales_qty

from

ranked

where sales_rank <= 20

Most candidates I talk to approach this without using a ranking function and end up doing something using limit, which, in my opinion, is a somewhat lazy and definitely not scalable solution - as we’ll see below when we extend this question.

How about the Top 20 Products in terms of Sales by Store?Permalink

This is where the limit N approach usually falls apart, but using the more generalizable approach above we can just extend what we were doing, like this:

-- first we need to aggregate our large fact table to the grain of interest,

-- in this case sales qty by product by store, over some time frame

-- (because we always want a date in DW World)

with sales as

(

select

p.product_name,

s.store_name,

sum(f.sales_qty) as sales_qty

from

fct_sales f

join

dim_product p on f.product_key = p.product_key

join

dim_store s on f.store_key = s.store_key

where

f.txn_date between

'some_date' and

'some_other_date'

group

1,2

),

-- then we rank the products for each store using a dense_rank() to avoid ties

-- (use your own business rules here)

ranked as

(

select

product_name,

store_name,

sales_qty,

dense_rank() over(

partition by store_name

order by sales_qty desc) as sales_rank

from

sales

)

-- then pick out the top N products (you could even do this in the BI layer)

select

store_name,

sales_rank,

product_name,

sales_qty

from

ranked

where sales_rank <= 20

Cumulative TotalPermalink

Cumulative Totals, or Running Sums are one of the most helpful analytical building blocks, whether it’s in sales forecasting or marketing cohort analysis. Like most SQL window functions, they can be partitioned so that we can calculate running sums within (or along) some subset/partition of data.

Let’s try a simple case first:

Cumulative Sales YTD:Permalink

-- Again, first we want to pre-aggregate to the grain we're interested in:

with daily_sales as

(

select

txn_date,

sum(sales_amt) as sales_amt

from

fct_sales

where

txn_date >= '2018-01-01'

group by

1

)

select

txn_date,

sales_amt,

sum(sales_amt) over(

order by txn_date rows unbounded preceding) as cumulative_sales_amt

from

daily_sales

The sum() window function here includes a key statement: rows unbounded preceding, which tells our db to to sum over all (unbounded) rows preceding the current one. The order by clause makes sure we’re tallying up sales cumulatively in chronological order.

Since we added a where clause specifying we’re only interested in sales data from Jan 1, 2018 on, this would constitute a YTD cumulative total, assuming we’re still in 2018.

[Note that there are better, more robust ways to construct that date logic, which we will “leave as an exercise for the reader”.]

If we wanted to compare YTD performance by day by store, we can specify store_name as a partition, like so:

Cumulative Sales YTD by Store:Permalink

-- As always, first we pre-aggregate to the grain we're interested in:

with daily_sales as

(

select

f.txn_date,

s.store_name,

sum(f.sales_amt) as sales_amt

from

fct_sales f

join

dim_store s on f.store_key = s.store_key

where

f.txn_date >= '2018-01-01'

group by

1,2

)

select

txn_date,

store_name,

sales_amt,

sum(sales_amt) over(

partition by store_name

order by txn_date rows unbounded preceding) as cumulative_sales_amt

from

daily_sales

This time, the sum() window function contains a partition by clause that tells us we want cumulative totals for each store over the transaction date.

Cumulative %Permalink

Many times, comparing absolute running totals only gets us so far, and what we really want is a cumulative % of total. For example, we may be interested in the trajectory of how a certain marketing cohort reached its ultimate conversion rate. (Btw, we’ll have a series of related blog posts on this soon, stay tuned!)

For this, we’ll need to combine window functions:

- one to calculate the cumulative total

- a second to calculate the grand total so that we can then divide the cumulative total by the grand total

Let’s stick with our example of cumulative totals by store and see if each store followed a similar sales trajectory so far this year.

Cumulative Sales % YTD by Store:Permalink

-- As always, first we pre-aggregate to the grain we're interested in:

with daily_sales as

(

select

f.txn_date,

s.store_name,

sum(f.sales_amt) as sales_amt

from

fct_sales f

join

dim_store s on f.store_key = s.store_key

where

f.txn_date >= '2018-01-01'

group by

1,2

)

select

txn_date,

store_name,

sales_amt,

-- Cumulative Total by Store

sum(sales_amt) over(

partition by store_name

order by txn_date rows unbounded preceding)::float/

-- Grand Total by Store

sum(sales_amt) over(partition by store_name)

as cumulative_sales_percentage

from

daily_sales

Let’s break down the last few lines:

sum(sales_amt) over(

partition by store_name

order by txn_date rows unbounded preceding)

This gets us the cumulative total of sales for each store over the entire date range, just like we calculated earlier.

The next line gets us the grand total for each store over the chosen date range:

sum(sales_amt) over(partition by store_name)

We then apply a lazy ::float conversion to the numerator to avoid integer division issues, before we divide to get the % contribution.

sum(sales_amt) over(

partition by store_name

order by txn_date rows unbounded preceding)::float/

sum(sales_amt) over(partition by store_name)

So, effectively, this tells how each day incrementally contributed to the store’s total sales over time since Jan 1.

Moving AveragesPermalink

A moving average is one of the best ways to smooth out a time series and to remove noise from short-term observations. For example, you may have weekly data and you’re interested in whether or not your data is trending on a larger time frame. A moving average can help you with that by giving you an additional, zoomed out view of your data with which you can now compare your weekly time series data. For similar reasons, moving averages also provide the basis for well-known time series forecast models, such as ARIMA.

In SQL, moving averages can be constructed by adding a window to the avg() function that specifies a rolling window over the rows. For instance, for a 4-week moving average (4WMA), we’re interested in the average over the last 4 rows of our, previously aggregated, weekly data.

-- As always, first we pre-aggregate to the grain we're interested in:

with weekly_sales as

(

select

d.week_start_date,

sum(f.sales_amt) as sales_amt

from

fct_sales f

join

dim_date d on f.txn_date = d.calendar_date

where

f.txn_date >= '2018-01-01'

group by

1

)

select

week_start_date,

sales_amt,

avg(sales_amt) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 3 preceding and current row) as sales_4wma

from

weekly_sales

This example includes the current week in the calculation of the moving average, hence we start with the 3 preceding rows.

However, often, you’re interested in the moving average of the N weeks before the current period, in which case we’d rewrite the avg() over a window of the prior 4 through 1 row:

...

avg(sales_amt) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 4 preceding and 1 preceding) as sales_4wma

...

Note: on the Snowflake data warehouse platform, the avg() function currently does not yet support adding a window, so we have to resort to a little hack - dividing a sum() by a count() function over the same window.

E.g.:

...

sum(sales_amt) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 4 preceding and 1 preceding)::float/

count(*) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 4 preceding and 1 preceding)

as sales_4wma

...

Moving Confidence IntervalsPermalink

Lastly, it’s very handy to be able to measure variance or standard deviation over a time series and construct a moving confidence interval (or at least approximating a confidence interval by assuming the variance in our data is normally distributed). We’ve already seen an application of moving confidence bands in our post on Confidence Intervals for Proportions where we looked at Bollinger Bands around a weekly order exchange rate example. To construct such a confidence band, we’ll need both a moving average and a moving standard deviation.

Luckily, on most data warehouse platforms, the stddev() function is also available as a window function, and we can simply apply what we’ve learned so far to stddev as well.

[Note: on Snowflake window support for stddev is still sadly missing, but I’ve been told this, along with other enhancements to their ANSI SQL support, is underway.]

Let’s start with the full query, then break it down later:

-- As always, first we pre-aggregate to the grain we're interested in:

with weekly_sales as

(

select

d.week_start_date,

sum(f.sales_amt) as sales_amt

from

fct_sales f

join

dim_date d on f.txn_date = d.calendar_date

where

f.txn_date >= '2018-01-01'

group by

1

),

moving_functions as

(

select

week_start_date,

sales_amt,

avg(sales_amt) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 4 preceding and 1 preceding) as sales_4wma,

stddev(sales_amt) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 4 preceding and 1 preceding) as sales_4wstd

from

weekly_sales

)

select

week_start_date,

sales_amt,

sales_4wma,

sales_4wma + 1.96*sales_4wstd as sales_upper_bound,

sales_4wma - 1.96*sales_4wstd as sales_lower_bound

from

moving_functions

Breaking this down a bit:Permalink

First, along with the moving average, we add another window function to capture the 4-week moving standard deviation of our sales metric (in this example, not including the current week).

...

stddev(sales_amt) over(

order by week_start_date

rows between 4 preceding and 1 preceding) as sales_4wstd

...

Then, we construct both upper and lower bounds by adding the moving standard deviation, multiplied a z-score (we chose 1.96 for a 95% confidence interval, see here) to the 4-week moving average. This essentially constructs a 95% confidence interval (approximated) around each 4-week moving slice of data.

...

sales_4wma + 1.96*sales_4wstd as sales_upper_bound,

sales_4wma - 1.96*sales_4wstd as sales_lower_bound

...

So, what have we learnedPermalink

There are many other ways to employ the power of window functions on a modern data warehouse platform that take advantage of the processing power of distributed/parallel systems. I really encourage new and experienced analysts to explore their SQL options before defaulting to using Python or R.

Using SQL as a structurally simple and easy to put-into-production technology to do advanced analytics, or to preprocess engineered features for your machine learning, is an essential tool in the analyst tool belt.

Comments